For the New Year

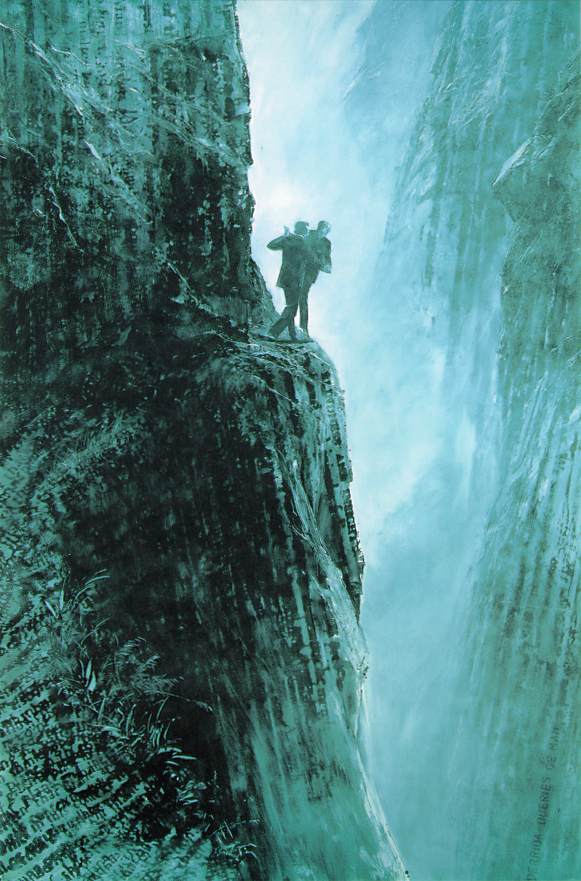

The image above is a panorama taken on the summit of Mauna Kea at sunset on January 1, 2018. I have long wanted to be at the summit at the time of a full moon at sunset in the hopes of seeing the sunset and moonrise at the same time. Since the exact full moon occurred only a few hours before sunset I thought it might be possible, and since it was New Years Day, it seemed perhaps an especially perfect day for a trip to the summit. Some might question whether it is at all appropriate however. There is a dispute regarding the summit of Mauna Kea. Rising to almost 14,000 feet in elevation in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, it is the highest peak in the Hawaiian Islands, and, indeed, in the whole Pacific. The summit is thus ideal for astronomy and thus one of the very best places on the planet for telescopes; but it is also perhaps the most sacred place in Hawaii, and the 'protectors of Mauna Kea' brought the construction of a new, state of the art, extra large telescope to a halt a couple of years ago, blocking the road in non-violent civil disobedience. As of this writing, there has been no resolution of the dispute and the fate of the telescope has not been determined. Some of my Hawaiian friends won't go to the summit except for a sacred ceremony, and thus the question arises whether it is possible to show respect for Hawaiian culture and still make the trip to the summit. I will have more to say about this later, for now I will just say that I went to the summit—with a deep appreciation for the sense of the sacredness of the place—in order to greet the New Year at the most auspicious place and time as that is what seems demanded of this day.

With what resolution shall I welcome the New Year? The road ahead looks perilous and not at all easy. If one is really honest in facing up to what is happening now, then it seems quite likely that every year from here on out is going to be worse than what came before—there will be more frequent and increasingly more devastating fires, storms, droughts, heat waves, famine, and other consequences of the changing climate. Let's face it, what John Lennon once said years ago—"Our society is run by insane people for insane objectives. I think we're being run by maniacs for maniacal ends"—is even more true today. Our whole civilization is headed toward catastrophe and there doesn't seem to be much reason for hope. I went to the sacred summit to try and summon the courage to face the future.

The sky was crystal clear above the clouds at the summit and there was still quite a bit of snow from the storm last week. The vistas in every direction are breathtaking. The great Mauna Loa, Mauna Kea's sister mountain, rises up almost to the same elevation, a crown of snow at the top. Hualalai, rising to about 8000 feet, peeks above the layer of clouds below. In another direction the great Haleakala, which makes up the island of Maui, rises above the blanket of clouds over the ocean. In another direction I can make out, just barely, the plume from the summit of Kilauea far below, ascending upward just a couple of miles from where I live. I wasn't sure whether I would be able to see both the sunset and moonrise at the same time from the same point, but then, just as I was watching the sunset, someone shouted and I turned and saw the Wolf Moon rising, large and full in the shadow of Mauna Kea.

It was indeed a most auspicious moment. I don't know what the New Year will bring, but I thought I would start with a little reflection on the Nietzsche's notion of amor fati, introduced in one of my favorite passages, presented as a New Year's resolution. Before I get to this reflection, however, I need to say a few things in general about Nietzsche's thought as an introduction for those who are not familiar with it.

The Masked Philosopher

Most people today still have no idea of Nietzsche's philosophy, especially in America where most people haven't the faintest grasp of the importance of philosophy; but this is hardly surprising since they have never even been introduced to the love of wisdom having been blinded since childhood by a faith that does not allow any real questioning. Most Americans don't have the courage for the love of wisdom; they want to rest comfortably on their beliefs and thus they seek out only the most pleasing and soothing ideas. Their "truths" are thus soft pillows to sleep on. They are thus especially unprepared for a thinker like Nietzsche for whom "truth is hard" and often not at all comforting.

Then there is the problem that those who have at least heard of Nietzsche only have some gross caricature in mind when they hear the name and thus they run away in terror. But even those who are not frightened away by faith shut their ears to Nietzsche lest they hear something that may disturb their slumber. And, unfortunately, it is probably safe to say that even most philosophers, at least in this country, don't have much of an understanding of Nietzsche's thought and thus cannot see its importance and relevance today. This is simply due to the fact that they have not been trained to deal with a thinker like Nietzsche. They are trained only to find lines of argument and thus don't have the sensitivity for a writer who has a sense of style, one who employs a multifaceted assortment of styles, which thus demands an attention to the nuances of voice and tone. They certainly don't know what to do with a thinker who would write:

The hermit does not believe that any philosopher—assuming that every philosopher was first of all a hermit—ever expressed his real and ultimate opinions in books: does one not write books precisely to conceal what one harbors? (Beyond Good and Evil, §289)

Most philosophers write books to try and win arguments. When one reads most philosophical books one can assume that the author is trying to convince the reader of something. They want the readers' assent and they will try to marshal the best and clearest arguments to compel that assent. With Nietzsche one should perhaps never make this assumption. He is often engaged in thought experiments, pursuing lines of inquiry in multiple directions, often questioning the unquestioned; he is indeed often tempting the reader to take up these experiments in thinking, yet he warns the reader also that these thoughts are sometimes perhaps dangerous, implying that they need to be handled most carefully. The opening lines of the last chapter of his strange autobiography perhaps should be taken as a warning:

I know my lot. Some day my name will be linked to the memory of something monstrous, of a crisis as yet unprecedented on earth, the most profound collision of consciences, a decision conjured up against everything hitherto believed, demanded, hallowed. I am not a man, I am dynamite. (Ecce Homo, "Why I am a Destiny" §1)

It should be easy to understand why Nietzsche goes on in this passage to explain: "there is nothing in me of a founder of religions . . . I don't want any disciples." About the same time he was penning these words, he writes to a friend: "It is not at all necessary or even desirable to side with me; on the contrary, a dose of curiosity . . . and an ironic resistance would be an incomparably more intelligent position to adopt." This need to keep the reader at bay so to speak, to undermine the reader's confidence that he or she has really understood Nietzsche's real and ultimate opinions, perhaps at least partly explains Nietzsche's play with masks, a frequent theme in his writings.

As I once put it in my dissertation long ago: "Nietzsche comes on the scene of postmodern thought like Dionysus, in The Bacchae, entering Thebes. The tragic play begins with Dionysus announcing his identity. He has come to 'reveal himself' to Pentheus and all of Thebes as 'the god I really am.' And yet Dionysus comes with his divine form exchanged for that of a mortal. That is, he comes masked. His identity is that of a masked god. Through the enigmatic mask his identity is both manifested and disguised. Nietzsche comes as the masked philosopher. His writings are full with the play of masks and veiled in their enigma." A good example of this play is this passage:

Everything profound loves a mask; the profoundest things of all even have a hatred of image and parable. Could it be that antithesis is the one proper disguise for the modesty of a god to stride forth in? A questionable question: it would be odd if some mystic had not ventured something to that effect. There are occurrences of such a delicate nature that one does well to cover them up with some rudeness to conceal them; there are actions of love and extravagant generosity after which nothing is more advisable that to take a stick and give any eyewitness a sound thrashing. . . A man whose sense of shame has some profundity encounters his destinies and delicate decisions, too, on paths which few ever reach and of whose mere existence his closest intimates must not know: his mortal danger is concealed from their eyes, and so is his regained sureness of life. Such a concealed man who instinctively needs speech for silence and for burial in silence and who is inexhaustible in his evasion of communication, wants and sees to it that a mask of him roams in his place through the hearts and heads of his friends. And supposing he did not want it, he would still realize some day that in spite of that a mask of him is there—and that this is well. Every profound spirit needs a mask; even more, around every profound spirit a mask is growing continually, owing to the constantly false, namely shallow, interpretation of every word, every step, every sign of life he gives. (Beyond Good and Evil, §40)

Part of the necessity of masks has to do with the problem of interpretation, as Nietzsche is explaining here. In the traditional view the aim of interpretation would be to pull away the mask and reveal the true face behind the mask. Nietzsche rejects and mocks the notion of a 'naked truth':

No this bad taste, this will to truth, to 'truth at any price,' this youthful madness in the love of truth, have lost their charm for us: for that we are too experienced, too serious, too merry, too burned, too profound. We no longer believe that truth remains truth when the veils are withdrawn; we have lived too much to believe this. Today we consider it a matter of decency not to wish to see everything naked, or to be present at everything, or to understand and 'know' everything. (The Joyful Science, Preface to the Second Edition §4)

The notion of the naked truth stripped of all interpretation is so deeply embedded in the Western tradition that most people simply assume there is no truth unless the veils are withdrawn. The idea is there in the archetypal journey of the philosopher, depicted in Plato's vision of the 'myth of the cave,' where the philosopher must somehow find his way out of the cave of the world of appearance to the upper world, the true world of the Forms. Even philosophers who reject Plato's world of the Forms still find Plato's notion of truth alluring. The naked truth is the objective truth. It provides a ground, something solid to build upon. It settles arguments because it demands assent. For Plato if we ever did discover the truth we would have to agree because truth provides a common ground. Long after Plato the assumption still underlies most philosophers conception of truth, sometimes even in the subtle ways when the philosophers least expect it.

Nietzsche's perspectivism challenges this traditional notion of truth. He calls Plato's notion of truth the "dogmatist's error," "the worst, most durable, and most dangerous of all errors" for "it meant standing truth on her head and denying perspective, the basic condition of all life, when one spoke of the spirit and good as Plato did" (Beyond Good and Evil, Preface). One of the most important aspects of Nietzsche's philosophy that the stereotypical view of Nietzsche in the common understanding doesn't get is the modesty of his thought.

This might seem strange to say of one who writes an autobiography with such chapter titles as "Why I Am So Wise," "Why I Am So Clever," "Why I Write Such Good Books," and, of course, the closing chapter "Why I Am A Destiny." The euphoric rapture of his exaltation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra in the autobiography would seem to seem to be the very antithesis of modesty. Of the 'Night-Song,' one of the five songs mixed in with the speeches of Zarathustra, the author writes: "Nothing like this has ever been composed, ever been felt, ever been suffered, this is how a god suffers, a Dionysus." At the end, when he explains that destiny, he explains that with the words that he put in the mouth of Zarathustra "he breaks the history of humanity in two." This euphoria is often simply dismissed as megalomania, a symptom of Nietzsche's madness, as it was only a few short weeks after completing the autobiography that Nietzsche's brilliant but feverish mind finally broke, shattering on the street in Turin. There is no doubt that Nietzsche suffered from delusions of grandeur, as the last mad letters attest, as well as the sad tale of the train ride when he is taken back to Basel for the medical examination. They were only able to get him on the train when they told him that there were receptions waiting for him including pageants and musical festivals held in his honor. When they stopped at a railway station to change trains he wanted to address the crowds and embrace everyone. After the examination in Basel the doctor's report reads: "Claims he is a famous man and asks for women all the time."

That is almost hilarious if it weren't so utterly tragic. Nevertheless, perhaps one misses something in simply dismissing what Nietzsche writes in the autobiography—the very title of the book, Ecce Homo would of course suggest delusions of grandeur—as mere symptoms of this madness. There are those who would dismiss not only the intense 'mad' writings of that last climatic year, but the whole of Nietzsche thought simply because of the end, that he wound up spending the last eleven years of his life completely insane in the care of his sister who completely misunderstood his work and monstrously distorted his legacy. Both dismissals are a mistake, I think, for I do think Nietzsche has something very important to say, something especially relevant in our time today, not only in peak years of his writings but right through to the last writings. Perhaps the exorbitant claims Nietzsche makes in Ecce Homo need to be taken seriously, but considering everything he had said about the necessity of the mask, perhaps the whole persona, voice, and tone of Ecce Homo is part of Nietzsche's play with masks.

Are the grandiose claims of Ecce Homo merely symptoms of megalomania or are they the final flickering brilliance of his lucidity? Perhaps they are both at once. In any case, what one misses if one's impression of Nietzsche comes only from such claims and exorbitant rhetoric—which although coming to an apotheosis in Ecce Homo runs through much of his writings—is the modesty of his thought. In that Preface to The Joyful Science in which he calls into question the idea of a naked truth he writes: "One should have more respect for the bashfulness with which nature has hidden behind riddles and iridescent uncertainties." The modesty of Nietzsche's perspectivism comes through in this much discussed passage from near the end of that book:

Our new "infinite."—How far the perspective character of existence extends or indeed whether existence has any other character than this; whether existence without interpretation, without "sense," does not become "nonsense"; whether, on the other hand, all existence is not essentially actively engaged in interpretation—that cannot be decided even by the most industrious and most scrupulously conscientious analysis and self-examination of the intellect; for in the course of this analysis the human intellect cannot avoid seeing itself in its own perspectives, and only in these. We cannot look around our own corner: it is a hopeless curiosity that wants to know what other kinds of intellects and perspectives there might be . . . But I should think that today we are at least far from the ridiculous immodesty that would be involved in decreeing from our corner that perspectives are permitted only from this corner. Rather has the world become "infinite" for us all over again, inasmuch as we cannot reject the possibility that it may include infinite interpretations. (The Joyful Science §374)

Nietzsche has often been considered a sort of postmodern prophet: in his anticipations of a 'philosophy of the future' he opens the door and in some sense inaugurates postmodern thought. The postmodern condition was once famously described by the French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard as an "increduility toward metanarratives." What Lyotard meant is a general suspicion regarding any attempts to tell the grand story, the 'ultimate and real' account of what it is all about, the meaning of existence, the final truth about reality. When Nietzsche raises the question, 'Why couldn't the world that concern us be a fiction?' he is raising that suspicion regarding metanarratives (Beyond Good and Evil, §34). There is no ultimate, final, naked truth because we cannot look around our own corner. There is no 'pure reason' that could reveal a truth without veils because all knowing involves an active interpretation from particular perspective points of view. This is also what Derrida meant by the controversial phrase 'il n'y a pas de hors-texte', often mistranslated as 'there is nothing outside the text' and thus misunderstood as the claim that there is nothing outside of language. What the phrase really says is that 'there is no outside-text' or, in other words, there is no truth without veils, no access to a reality that is not already a product of interpretation. The modesty of Nietzsche's 'philosophy of the future' is then to acknowledge that the world that concerns us is a fiction, a product of interpretation. There may be narratives, stories we tell ourselves about the point of it all and the nature of existence, but no 'ultimate and real' story or 'metanarrative.'

It is due to the fear that this position ultimately leads to nihilism that many philosophers want to reject Nietzsche's philosophy and its postmodern heirs, and it also leads some scholars, those who don't want to reject Nietzsche, even some of the best Nietzsche scholars, to try and find passages in which Nietzsche seems to pull back from his customary perspectivism. I guess I don't think this is such a good strategy because it requires overlooking the general tenor of Nietzsche's mature thought that emphasizes that there is no getting around perspectivism. It seems to miss perhaps the most important reason why Nietzsche considered the high point of Greek culture to be not Socrates and Plato, but Aeschylus and Sophocles. With their optimistic view that truth is beautiful, that there is a truth that is not a fiction and thus is capable of providing a common ground that would resolve all disagreement, the philosophers brought about the death of Greek Tragedy by pulling the gaze of the Greeks from confronting the abyss, the abysmal truth that there is no such truth.

Returning again to the hyperbolic language of the autobiography Nietzsche writes: "I know abysses into which no foot has yet strayed" (Ecce Homo, "Why I Write Such Good Books, §3). I think instead of pulling Nietzsche back from the abyss, one has to follow his thought there and thus try to understand why Greek Tragedy, and especially the figure of Dionysus, was so important to Nietzsche from his first book right on through to the very last writings. I don't think Nietzsche ever departs from the view expressed by his hermit philosopher who suggests that he writes books precisely to conceal. In the rest of the passage we see Nietzsche's critique of Plato, the suspicion of metanarratives, and the metaphor of the mask all come together:

Indeed he will doubt whether a philosopher could possibly have 'ultimate and real' opinions, whether behind every one of his caves there is not, must not be, another deeper cave—a more comprehensive, stranger, richer world beyond the surface, an abysmally deep ground behind every ground, under every attempt to furnish 'grounds.' Every philosophy is a foreground philosophy—that is a hermit's judgment: 'There is something arbitrary in his stopping here to look back and look around, in his not digging deeper here but laying his spade aside; there is also something suspicious about it.' Every philosophy also conceals a philosophy; every opinion is also a hideout, every word also a mask. (Beyond Good and Evil, §289)

If one has grasped what I have been trying to suggest about Nietzsche's philosophy, perhaps one might understand why I might feel slightly bemused and only smile when I hear my friends, even my bright philosophical friends, explain what they don't like about Nietzsche's philosophy. Following some line of argument they will confidently explain where Nietzsche went wrong. Considering the sometimes-dangerous experimental thinking he often engaged in, it is actually easy to find something wrong somewhere with what Nietzsche wrote. It is, of course, important and in some cases absolutely necessary to do so. After all, Nietzsche didn't want disciples, and he gave many warnings to discourage such followers. But if one thinks that one has thus determined what Nietzsche's 'ultimate and real' position is, and thus unmasked Nietzsche, one probably never really grasped what is most important and interesting about his thought. Returning again to the autobiography, it is perhaps worthwhile to remember what he said regarding those who too confidently thought they understood him:

Ultimately no one can hear in things—books included—more than he already knows. If you have no access to something from experience, you will have no ear for it. . . . Ultimately this is my average experience and, if you will, the originality of my experience. Those who thought they understood me have turned me into something else, in their own image—not uncommonly into an opposite of me. (Ecce Homo, Why I Write Such Good Books, §1).

Perhaps the most unfortunate thing that results from too confidently thinking that one has understood his thought and found what was wrong about it, is that one misses a lot that is worth trying to understand. I think it is worth trying to understand his critique of some of the fundamental assumptions of the Western tradition of philosophy—especially his interrogations regarding truth and the problem of morality—as well as his attempts to make a radical break from that tradition—and thus his reconsideration of the relationship between art and truth, his suggestion that the countermovement to nihilism is through art, and thus the importance, once again, of what he saw in Greek Tragedy and in the figure of Dionysus. If one dismisses Nietzsche too hastily one misses a lot of really great stuff, and this thought of amor fati with which he greets the New Year is a really good example.

Amor Fati

Perhaps the thing to grasp first about the passage is that it is a New Year's resolution. It is an aspiration. It is not as if he is writing from the perspective of one who has already accomplished something. His use of the Latin phrase amor fati, meaning simply 'love fate', is surely a nod to the Roman Stoic philosophers. Epictetus, the slave who rose to become a respected philosopher of the day expresses the thought well: "Do not seek to have events happen as you want them to, but instead want them to happen as they do happen, and your life will go well" (The Handbook, §8). Marcus Aurelius, the emperor who took the words of Epictetus to heart, also expresses the thought in describing how philosophy can help us on our way: "This consists in guarding our inner spirit inviolate and unharmed, stronger than pleasures and pains, never acting aimlessly, falsely or hypocritically, independent of the action or inaction of others, accepting all that happens or is given as coming whence one came oneself" (Meditations, 2, §17). The thought of amor fati is connected for Nietzsche with the thought of eternal recurrence, the central thought of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the book that would divide humanity in two—between what came before and what comes after—and this thought is also suggested by Marcus Aurelius: "When you find something hard to tolerate, you have forgotten that everything happens in accord with the nature of the Whole; that the wrong done to you is another's concern; and further, that everything which happens has always happened so, and will so happen, and is happening now, everywhere" (Meditations, 22, §26).

Marcus Aurelius

Nietzsche was certainly influenced by the Stoics, from all accounts there was certainly an element of Stoicism in his character, and there are echoes of Stoicism throughout his writings; nevertheless, this influence must be considered alongside Nietzsche's critique of ascetic ideals and his fixation on Dionysus. The Stoics also emphasized the elimination of desires as much as possible. Epictetus advises: "And for the time being eliminate desire completely, since if you desire something that is not up to us, your are bound to be unfortunate" (The Handbook, §2). This element of Stoicism certainly had an influence on the development of Christianity and Nietzsche harshly criticized the ascetic ideals in Christianity in his Genealogy of Morals as symptoms of a denial of life.

His New Year's resolution might be said to express his most important thought, his aspiration to one day be capable of the affirmation of life, to be 'only a Yes-sayer.' One might even say that this is Nietzsche's 'ultimate and real' opinion—except, of course, one would have to be mindful of his hermit's judgment that would caution against this. Still, so much of his work focuses, on the one hand, on exposing the ascetic ideals and denial of life in the hidden history of philosophy, and, on the other, with the affirmation of life. The whole of Zarathustra is about becoming capable of fulfilling this New Year's resolution to say 'yes' to life. His fascination with Dionysus was also about this affirmation of life. Whereas the Stoics emphasized the extirpation of desires in order to become capable of amor fati, Nietzsche emphasized the importance of ecstatic experience that he associated with Dionysus.

In the autobiography the masked philosopher constantly plays at revealing himself. Since the book was the last work that he finished shortly before his collapse, the last words of the final chapter, "Why I Am A Destiny," might be regarded as the last words of the writer Nietzsche:

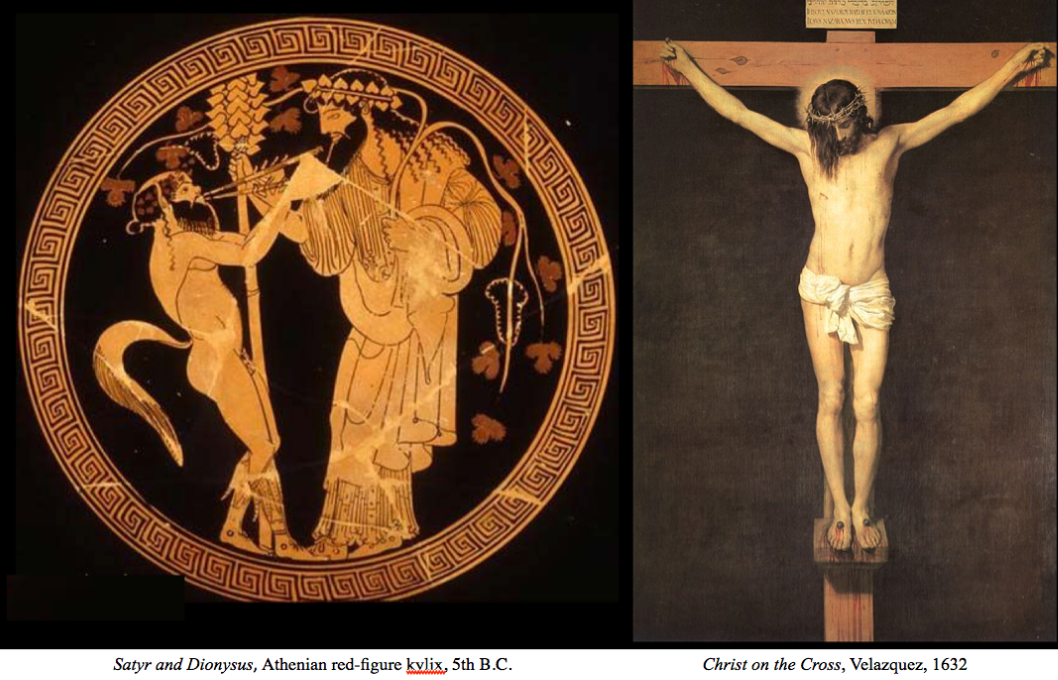

Have I been understood?—Dionysus versus the Crucified.—

Dionysus versus the Crucified

Did the masked philosopher finally unmask himself here at the end with his last words? Perhaps. But Dionysus, of course, is the masked god; and then, the whole phrase 'Dionysus versus the Crucified' is also a mask. It would be wrong to think this is simply an opposition between the Greek god and the one who died on the cross. 'Dionysus' and 'the Crucified' are both signs—they refer to themes that developed over a long period through Nietzsche's writings. One could get some sense of what he means by 'the Crucified' by reading the "Attempt at a Self-Criticism' he appends as a preface to his first work, The Birth of Tragedy, fourteen years after its initial publication. There he writes:

In truth, nothing could be more opposed to the purely aesthetic interpretation and justification of the world which are taught in this book than the Christian teaching, which is, and wants to be, only moral and which relegates art, every art, to the realm of lies: with its absolute standards, beginning with the truthfulness of God, it negates, judges, and damns art. Behind this mode of thought and valuation, which must be hostile to art if it is at all genuine, I never failed to sense a hostility to life—a furious, vengeful antipathy to life itself: for all of life is based on semblance, art, deception, points of view, and the necessity of perspectives and error. (The Birth of Tragedy, 'Attempt at a Self-Criticism, §5).

The opposition could thus be 'art versus truth'—at least Plato's truth, for it was Plato that relegated art to the realm of lies, and it was also in Plato that Nietzsche sensed a hostility to life—especially in Plato's portrayal of Socrates' last words. Christianity absorbed Plato's truth, as well as the hostility to life, and then developed this hostility, insidiously, throughout the history of its development. One only has to remember such things as the medieval torture chambers and the burning fires that roasted human beings alive during the Inquisition to see Nietzsche's point. But one might also think of that psychological torture experienced by countless human beings through the centuries as a result of the hostility to life that worked its way through Christian morality. Everything natural to human beings became sinful; the body became a source of evil, and along with it, the rest of Nature. In the longing for another world, life on earth becomes condemned. Just think of the Christians today who look forward to the end of the world confident of their salvation (confidant as well that others, who don't share the same beliefs, will burn in hell forever). The refusal to recognize human responsibility for global warming and the resulting climate catastrophe that may well literally burn up the whole ecosystem leading to the extinction of human beings—and most life on earth—may also be a symptom of this in some cases.

The irony is that 'the Crucified' may not have anything to do with the one who died on the cross. Who was that person? Does anyone really know? Some question whether he even existed, but in any case, even if he did exist, he didn't leave us any writings to ponder what he may have meant. What we have are sayings attributed to him and stories told about him in texts written a generation of two afterwards. The stories of the 'life of Christ' told in the Gospels are fictions. They may have been based on events that really happened, but the narrative is already a product of interpretation as all narratives must be. We now know that there were many "Gospels" written in the early years of Christianity and it was not until the 4th century that the New Testament was put together. There is no metanarrative; but Christianity presents its story, the texts that were selected then by human beings for inclusion in the New Testament, as the actual 'word of God,' the absolute truth, denying its fictional status and thus denying, once again, art. It is this story, this narrative that Nietzsche is obviously referring to with his last words marking the opposition between 'Dionysus' and 'the Crucified.'

In The Antichrist, another one of the books from Nietzsche's last year, written just before the autobiography, Nietzsche offers a different story. He emphasizes that the Christian story is based on the death on the cross—hence 'the Crucified'—and the meaning of that death, its promise of eternal reward, while his story will be based on the life and the meaning of the life. Christianity took the death on the cross and made up a religion that promises eternal reward in exchange for correct belief or faith (and eternal damnation in the fires of hell for those that don't accept the story). In Nietzsche's counter-narrative, he presents a different 'evangel,' emphasizing not faith and the promise of eternal reward, but rather practice, a different way of living.

In the whole psychology of the “evangel” the concept of guilt and punishment is lacking; also the concept of reward. “Sin”—any distance separating God and man—is abolished: precisely this is the glad tidings.” Blessedness is not promised, it is not tied to conditions: it is the only reality—the rest is a sign with which to speak of it.

The consequence of such a state projects itself into a new practice, the genuine evangelical practice. It is not a “faith” that distinguishes the Christian: the Christian acts, he is distinguished by acting differently: by not resisting, either in words or in his heart, those who treat him ill; by making no distinction between foreigner and native. . .

The life of the Redeemer was nothing other than this practice—nor was his death anything else. He no longer required any formulas, any rites for his intercourse with God—not even prayer. He broke with the whole Jewish doctrine of repentance and reconciliation; he knows that it is only in the practice of life that one feels “divine,” “blessed,” “evangelical,” at all times a “child of God.” Not “repentance,” not “prayer for forgiveness,” are the ways to God: only the evangelical practice leads to God, indeed, it is “God”! . . .

The deep instinct for how one must live, in order to feel oneself “in heaven,” to feel “eternal,” while in all other behavior one decidedly does not feel oneself “in heaven”—this alone is the psychological reality of “redemption.” A new way of life, not a new faith. (The Antichrist, §33)

In Nietzsche's counter-narrative Christ is a 'symbolist' and thus when he used such phrases as "the son of man," "the kingdom of God," or the "kingdom of heaven," he was speaking symbolically. The "kingdom of heaven" is thus not some place one goes to after death, an eternal reward for the faithful, but rather something that is possible in any given moment:

The “kingdom of heaven” is a state of the heart—not something that is to come “above the earth” or “after death.” The whole concept of natural death is lacking in the evangel: death is no bridge, no transition; it is lacking because it belongs to a wholly different, merely apparent world, useful only insofar as it furnishes signs. The “hour of death” is no Christian concept—an “hour,” time, physical life and its crises do not even exist for the teacher of the “glad tidings.” The “kingdom of God” is nothing that one expects; it has no yesterday and no day after tomorrow, it will not come in “a thousand years”—it is an experience of the heart; it is everywhere, it is nowhere. (The Antichrist, §34)

I think this is one of the most beautiful passages in all of Nietzsche's writings. The message of the life of Christ, Nietzsche suggests here, is not about some eternal reward but rather about an experience of the heart. The 'evangel' is not offering an eternal reward in exchange for correct belief, but rather showing one how to live:

This “bringer of glad tidings” died as he had lived, as he had taught—not to “redeem men” but to show how one must live. This practice is his legacy to mankind: his behavior before the judges, before the catchpoles, before the accusers and all kinds of slander and scorn—his behavior on the cross. He does not resist, he does not defend his right, he takes no step which might ward off the worst; on the contrary, he provokes it. And he begs, he suffers, he loves with those, in those, who do him evil. Not to resist, not to be angry, not to hold responsible—but to resist not even the evil one—to love him. (The Antichrist, §35)

The basic point of The Antichrist, Nietzsche's counter-narrative about the 'life of Christ', is that Christianity basically turned this message of love around to its opposite. Of course Christians will protest with vehement hostility that Christ's message is about love and that is what Christianity teaches. But is this really evident in Christian practice today? Is this really evident in the conservative political agenda that fundamentalist and evangelical Christians today so fervently support? Are these Christians really trying to follow the example set by the one who Nietzsche describes here as loving even his enemies in his last painful dying breaths or are they really only interested in their own private fortunes and personal salvation?

Nietzsche saw something monstrous developing among the pious Germans of his day and he often harshly criticized their patriotic fervor and their antisemitism. Nietzsche's critique of Christianity is understood by only a few today. If they have any idea of Nietzsche's philosophy at all it is probably the line "God is dead," which they don't understand at all and simply dismiss as a mere atheism. But Nietzsche's critique doesn't really have anything to do with whether or not a God really exists. He really only makes jokes about this. His critique is rather that Christianity has turned Christ's message of love around to its opposite. His claim is that the whole of Christianity may have been a misunderstanding. He claims to tell the 'genuine' history of Christianity, but we know he must have been joking here too, mocking the Christian teaching that their story is the actual 'word of God' and thus the naked truth of the matter. I suspect, anyway, that he is using the word 'genuine' as a foil in his polemic against the lies of millennia. The point of The Antichrist is that it is Christianity that is really the 'Antichrist'. This is at least partly what he means in revealing his identity through the opposition between 'Dionysus' and 'the Crucified.' It is why he would have the audacity to title his 'autobiography' Ecce Homo, the Latin phrase, from the Vulgate translation of John 19:5, meaning 'behold the man'—the words used by Pontius Pilate in presenting Christ to the people before the crucifixion. It is why he would have the audacity to say in that book that his writings, especially Zarathustra, would divide humankind in two. Is not 'the Crucified'—this story concocted by the Church fathers—what divided history into what came before and after? Nietzsche would attempt to expose the lies and thus divide history again. Was it madness, mere megalomania that would lead Nietzsche to try and explain in the autobiography "Why I am a destiny"?

I go back, I tell the genuine history of Christianity. The very word “Christianity” is a misunderstanding: in truth, there was only one Christian, and he died on the cross. The “evangel” died on the cross. What has been called “evangel” from that moment was actually the opposite of that which he had lived: “ill tidings,” a dysangel. It is false to the point of nonsense to find the mark of the Christian in a “faith,” for instance, in the faith in redemption through Christ: only Christian practice, a life such as he lived who died on the cross, is Christian.

Such a life is still possible today, for certain people even necessary: genuine, original Christianity will be possible at all times. Not a faith, but a doing; above all, a not doing of many things, another state of being. (The Antichrist, §39)

What is perhaps really interesting here, however, is his acknowledgment that a life that really follows the example set by the life of Christ is still possible. The only thing is it involves a different state of being. Is it a state of being human beings are really capable of yet? Is love a gift or really just an investment, another selfish desire? This is a question raised at the outset of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. The story that unfolds in the book, and the speeches that Zarathustra gives, and the songs that he sings, are all about a transformation, or further evolution of humanity that must come if humankind is going to avoid a catastrophe in the future. It is perhaps now more than ever evident what Nietzsche may have been warning us about. Are human beings really going to become capable of following the example of the life of the one who died on the cross? Are we capable of being truly loving human beings, capable of the gift-giving love?

Greek Tragedy

"Mortal fate is hard. You'd best get used to it."

- Euripides, "Medea"

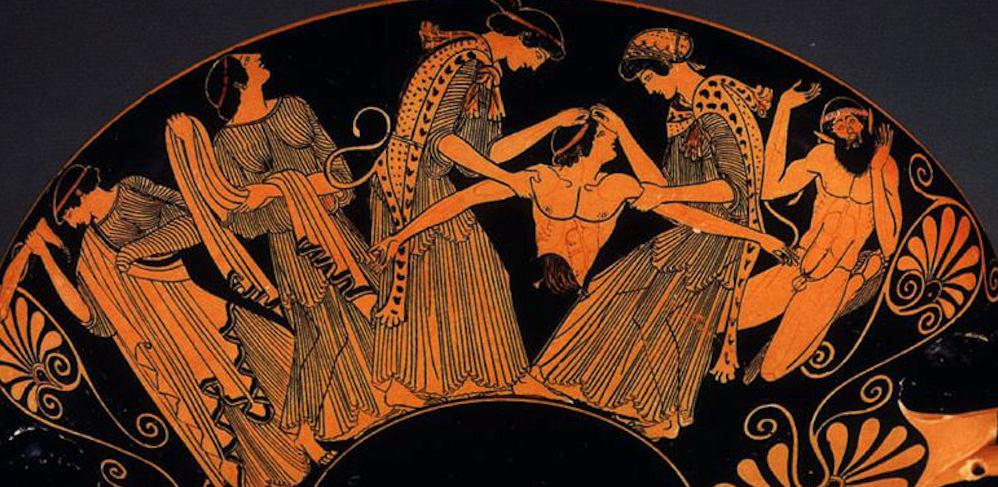

Nietzsche suggests, at the end of the fourth book of The Joyful Science that Thus Spoke Zarathustra is a tragedy. This may seem strange, as the book does not really have the form of a tragedy. The reason he suggests this, I suspect, is that he aimed to do in Zarathustra what he thought was the aim of Greek Tragedy. At the end of The Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche opens the door to modern art by suggesting that art need not be restrained by the task of imitation of the reality of nature which it had always been saddled with since Plato had condemned art to the realm of lies, only capable of making poor copies of things. But there he also suggests that the aim of art, attained in Greek Tragedy—and thus another reason why Aeschylus and Sophocles were the high point of Greek culture—is its capacity for transformation. The highest aim of art, Nietzsche suggests, is its capacity to change us. In The Birth of Tragedy, the Dionysian element Nietzsche saw in Greek Tragedy was, at least in part, this power of transformation.

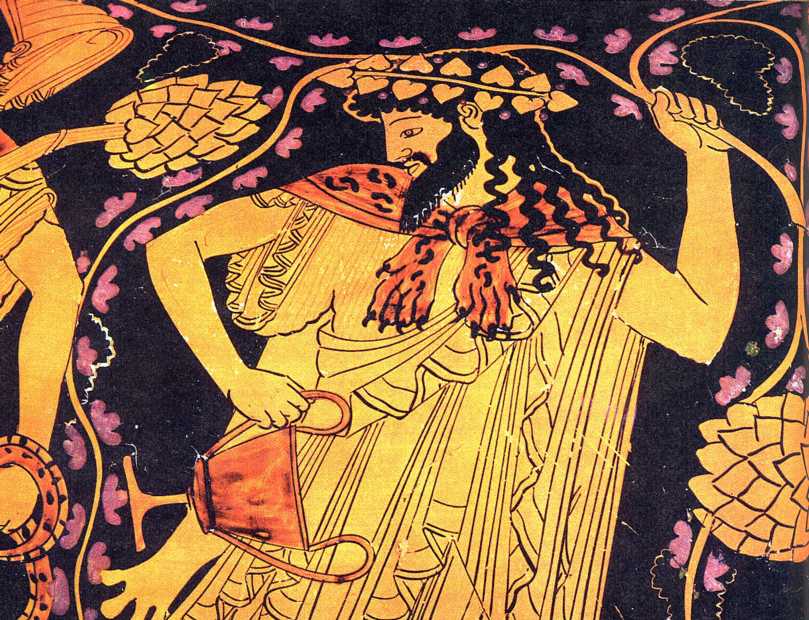

In Greek mythology, Dionysus was a god that had this power of transformation. This power is suggested, for example, in the famous depiction of Dionysus sailing upon the sea surrounded by dolphins, which is found on an ancient Greek ceramic kylix, a vessel for drinking wine. As one drank the wine the image of Dionysus and the dolphins would emerge. The image comes from a story in which Dionysus is captured by pirates. They don't realize whom they have accosted, but then vines laden with grapes sprout from the masts of the sailing vessel and the pirates are then transformed into dolphins. Throughout his writings Nietzsche often plays with imagery drawn from ancient stories about Dionysus.

While the last passage from book four of The Joyful Science connects Zarathustra with Dionysus and this power of transformation, the first passage of that book is the New Year's resolution and the introduction of the thought of amor fati. One can certainly see an echo of Stoicism in Nietzsche's preoccupation with the themes of fate and destiny. Does the notion of destiny and the 'love of fate' an indication of a fatalism in Nietzsche's thought as some have suggested? I think the notion of amor fati is for Nietzsche another thought experiment, one like the thought of eternal recurrence that is designed to bring about a transformation of human beings. As he puts it in his New Year's resolution, once he can accept what is necessary in things, then "I shall be one of those who makes things beautiful."

This suggests an interesting resonance with the ancient Chinese Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi with whom Nietzsche was most likely not familiar. A central theme in the Zhuangzi concerns the acceptance of fate or circumstance (命 ming), sometimes expressed as the 'destiny of heaven' (天命 tian ming), perhaps best understood as the 'circumstance decreed by the cosmos or the nature of things.' A number of Zhuangzi's stories, often presented with a striking sense of humor, involve characters that have suffered some misfortune, but are shown to be wiser than even Confucius in the way they have accepted their circumstance. A good example is the story of the ugliest man; he was ugly enough to astound the whole world, but men and women were drawn to him, with women even preferring to be "this gentleman's concubine than another man's wife!" The secret of the ugliest man, as Zhuangzi explains, is that he understood how to accept the workings of fate without it destroying his spirit:

Life, death, preservation, loss, failure, success, poverty, riches, worthiness, unworthiness, slander, fame, hunger, thirst, cold, heat—these are the alterations of the world, the workings of fate (命 ming). Day and night they change place before us and wisdom cannot spy out their source. Therefore, they should not be enough to destroy your harmony; they should not be allowed to enter the storehouse of spirit. If you can harmonize and delight in them, master them and never be at a loss for joy, if you can do this day and night without break and make it be spring with everything, mingling with all and creating the moment within your own mind—this is what I call being whole in power (德 de). (Zhuangzi, §5)

Is it possible that in accepting what is necessary in things, one can overcome the hostility to life and become a 'yes-sayer,' one of those capable of a gift-giving love who thus makes things beautiful, or in Zhuangzi's wonderful phrase "makes it be spring with everything"? Is it true, as The Beatles sang, in what became something of an anthem of the 60s, that "all you need is love"? I remember when I first encountered this Nietzsche that I thought there was an interesting resonance, but I didn't think there really could be a connection. But recently I learned from a documentary I saw that a friend remembers an incident when John Lennon walked into a London bookstore looking for works by Nietzsche. Did he ever really read Nietzsche? I am not sure if anyone can answer that, but I have wondered if there was some connection in songs like Mind Games:

We're playing those mind games together

Pushing the barriers planting seeds

Playing the mind guerrilla

Chanting the Mantra peace on earth

We all been playing those mind games forever

Some kinda druid dudes lifting the veil

Doing the mind guerrilla

Some call it magic the search for the grail

Love is the answer and you know that for sure

Love is a flower

You got to let it, you gotta let it grow

So keep on playing those mind games together

Faith in the future out of the now

You just can't beat on those mind guerrillas

Absolute elsewhere in the stones of your mind

Yeah we're playing those mind games forever

Projecting our images in space and in time

Yes is the answer and you know that for sure

Yes is surrender

You got to let it, you gotta let it go

So keep on playing those mind games together

Doing the ritual dance in the sun

Millions of mind guerrillas

Putting their soul power to the karmic wheel

Keep on playing those mind games forever

Raising the spirit of peace and love

I have often thought about Nietzsche's New Year's resolution over the years and especially in this last year, a year marked by the nightmare of Trump's Presidency and more ominous signs of the climate catastrophe that is unfolding, as well as the increasingly likely use of nuclear weapons in war. Most people still seem to be oblivious to it all despite the unprecedented storms and fires that are the result, climate experts assure us, of the global warming that has resulted from the burning of fossil fuels. Most scientists have been sounding the alarm, warning us that the problem is far worse than most people seem to realize. Some think that we are already past the tipping point where climate change becomes irreversible and that we might thus only have a few years left. What would be the point of it all if human existence came to an end due to greed and stupidity? Is it really possible to accept all that happens as necessary?

When I was a grad student I had the opportunity to do some research for a screenplay for a National Endowment for Humanities grant project on Nietzsche's life and thought. The film never got made as I guess the folks at NEH didn't think it was relevant and important enough for Americans today. I remember envisioning an opening scene in which Nietzsche stares out with fury upon the good pious Germans who paid admission to his sister to have a gaze at the mad philosopher. Apparently she had him dressed in a toga for the occasions. Would Nietzsche have been capable of amor fati then if he were aware of his fate, that his name would indeed be linked to the memory of something monstrous due to his sister's manipulations, that all his writings would be misunderstood and eventually come to naught as humanity slithers onward toward catastrophe?

I have often thought about amor fati in my life. I have often felt a profound weariness with life, battling against loneliness and despair, poor health, mounting debt, and an ever-increasing burden of work. It has often been a challenge to find the strength to say 'yes' to life. It seems like lately it has been a 'perfect storm' of difficulties. The task ahead seems so daunting I really don't know how I will get through it. But I will try to see as beautiful what is necessary in things and not give in to despair. Amor fati is my New Year's resolution every year.